Australian mathematician reveals world’s oldest example of applied geometry

5 August, 2021

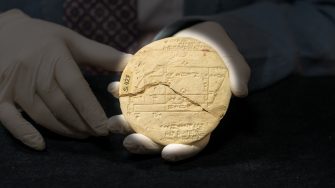

A UNSW Sydney scientist has revealed that an ancient clay tablet could be the oldest and most complete example of applied geometry. The surveyor’s field plan from the Old Babylonian period shows that ancient mathematics was more advanced than previously thought.

A UNSW mathematician has revealed the origins of applied geometry on a 3700-year-old clay tablet that has been hiding in plain sight in a museum in Istanbul for over a century.

The tablet – known as Si.427 – was discovered in the late 19th century in what is now central Iraq, but its significance was unknown until the UNSW scientist’s detective work was revealed today.

Most excitingly, Si.427 is thought to be the oldest known example of applied geometry – and in the study released today in the Foundations of Science, the research also reveals a compelling human story of land surveying.

“Si.427 dates from the Old Babylonian (OB) period – 1900 to 1600 BCE,” says lead researcher Dr Daniel Mansfield from UNSW Science’s School of Mathematics and Statistics.

“It’s the only known example of a cadastral document from the OB period, which is a plan used by surveyors to define land boundaries. In this case, it tells us legal and geometric details about a field that’s split after some of it was sold off.”

This is a significant object because the surveyor uses what are now known as “Pythagorean triples” to make accurate right angles.

“The discovery and analysis of the tablet have important implications for the history of mathematics,” Dr Mansfield says. “For instance, this is over a thousand years before Pythagoras was born.”

Si.427 is a hand tablet from 1900-1600 BC, created by an Old Babylonian surveyor. It’s made out of clay and the surveyor wrote on it with a stylus.

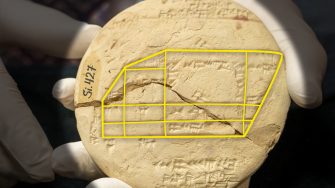

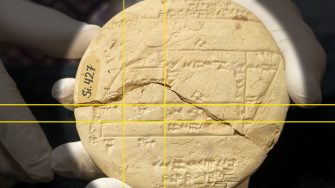

On the front, we see a diagram of a field.

The field is being split, and some of it is being sold.

That’s what the lines are for – they demarcate the boundaries of the different fields. The boundaries are really accurate – a lot more accurate than you’d expect for that time.

Our surveyor managed to be so precise by using Pythagorean triples – making the boundary lines he created truly perpendicular. In the simplest example of a Pythagorean triple, a triple has sides of 3, 4 and 5 – creating a perfect right angle.

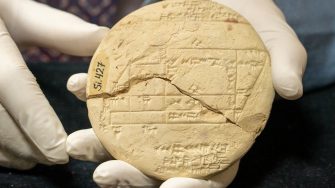

On the back of the tablet we see text, written in cuneiform, one of the earliest systems of writing.

The text corresponds to the diagram on the front – describing things such as the size of the field.

At the bottom of the back of the tablet, we see large numbers – that’s the only thing we haven’t quite figured out.

In 2017, Dr Mansfield conjectured that another fascinating artefact from the same period, known as Plimpton 322, was a unique kind of trigonometric table.

“It is generally accepted that trigonometry – the branch of maths that is concerned with the study of triangles – was developed by the ancient Greeks studying the night sky in the second century BCE,” says Dr Mansfield.

“But the Babylonians developed their own ‘proto-trigonometry’ to solve problems measuring the ground, not the sky.”

The tablet revealed today is thought to have existed even before Plimpton 322 – in fact, surveying problems likely inspired Plimpton 322.

“There is a whole zoo of right triangles with different shapes. But only a very small handful can be used by Babylonian surveyors. Plimpton 322 is a systematic study of this zoo to discover the useful shapes,” says Dr Mansfield.

Back in 2017, the team speculated about the purpose of Plimpton 322, hypothesizing that it was likely to have had some practical purpose, possibly in the construction of palaces and temples, building canals or surveying of fields.

“With this new tablet, we can actually see for the first time why they were interested in geometry: to lay down precise land boundaries,” Dr Mansfield says.

“This is from a period where land is starting to become private – people started thinking about land in terms of ‘my land and your land’, wanting to establish a proper boundary to have positive neighbourly relationships. And this is what this tablet immediately says. It's a field being split, and new boundaries are made.”

There are even clues hidden on other tablets from that time period about the stories behind these boundaries.

“Another tablet refers to a dispute between Sin-bel-apli – a prominent individual mentioned on many tablets including Si.427 – and a wealthy female landowner,” says Dr Mansfield.

“The dispute is over valuable date palms on the border between their two properties. The local administrator agrees to send out a surveyor to resolve the dispute. It is easy to see how accuracy was important in resolving disputes between such powerful individuals.”

Dr Mansfield says the way these boundaries are made reveals real geometric understanding.

“Nobody expected that the Babylonians were using Pythagorean triples in this way,” Dr Mansfield says. “It is more akin to pure mathematics, inspired by the practical problems of the time.”

One simple way to make an accurate right angle is to make a rectangle with sides 3 and 4, and diagonal 5. These special numbers form the 3-4-5 “Pythagorean triple” and a rectangle with these measurements has mathematically perfect right angles. This is important to ancient surveyors and still used today.

“The ancient surveyors who made Si.427 did something even better: they used a variety of different Pythagorean triples, both as rectangles and right triangles, to construct accurate right angles,” Dr Mansfield says.

However, it is difficult to work with prime numbers bigger than 5 in the base 60 Babylonian number system.

“This raises a very particular issue – their unique base 60 number system means that only some Pythagorean shapes can be used,” Dr Mansfield says.

“It seems that the author of Plimpton 322 went through all these Pythagorean shapes to find these useful ones.

“This deep and highly numerical understanding of the practical use of rectangles earns the name ‘proto-trigonometry’ but it is completely different to our modern trigonometry involving sin, cos, and tan.”

Dr Mansfield first learned about Si.427 when reading about it in excavation records – the tablet was dug up during the Sippar expedition of 1894, in what’s the Baghdad province in Iraq today.

“It was a real challenge to trace the tablet from these records and physically find it – the report said that the tablet had gone to the Imperial Museum of Constantinople, a place that obviously doesn’t exist anymore.

“Using that piece of information, I went on a quest to track it down, speaking to many people at Turkish government ministries and museums, until one day in mid 2018 a photo of Si.427 finally landed in my inbox.

“That's when I learned that it was actually on display at the museum. Even after locating the object it still took months to fully understand just how significant it is, and so it's really satisfying to finally be able to share that story.”

Next, Dr Mansfield hopes to find what other applications the Babylonians had for their proto-trigonometry.

There’s just one mystery left that Dr Mansfield hasn’t unlocked: on the back of the tablet, at the very bottom, it lists the numbers ‘25,29’ in big font – think of it as 25 minutes and 29 seconds.

“I can’t figure out what these numbers mean – it’s an absolute enigma. I’m keen to discuss any leads with historians or mathematicians who might have a hunch as to what these numbers trying to tell us!”

To syndicate this article or request an interview with Dr Mansfield, contact Isabelle Dubach, News & Content Manager, by phone on +61 (0) 432 307 244 or email at i.dubach@unsw.edu.au.

Story: Isabelle Dubach

Video: Lee Henderson, Brad Hall, Ralph Stevenson

Multimedia production: Taryn Anderson, Deborah Bordeos, Paul Casey, Marco Dos Santos, Isabelle Dubach, Tom Gibson, Peter Harrison, Emma Hayes, Mitch Lamm, Richie The, Oliver Watt